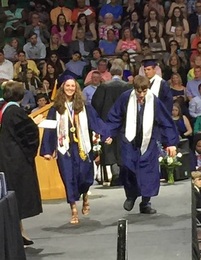

Teen Goes to Extraordinary Lengths to Give Autistic Twin a High School Graduation to Remember6/25/2015  Aly and her brother crossing the stage during graduation Aly and her brother crossing the stage during graduation A teenager has earned herself an army of fans after she finally reached her goal to help her severely autistic twin brother across the stage at their high school graduation. Anders Bonville, 18, from Birmingham, Alabama, was diagnosed with autism when he was two, which left him non-verbal but – along with his sister, Aly – the pair developed their own unique language and set out to alter perceptions of the condition. When the siblings first started school, Aly told AutismSpeaks how the other children in their class excluded Anders because he was “different.” She remembered: “Having grown up with Anders, I couldn’t imagine not having him be part of classroom activities and so my mother and I made sure to always introduce him to other students and have him give them high-fives. “Then, they would realized that – even though Anders has autism and couldn’t talk to them and made weird noises – he was just a kid like they were.” There was a brief period when the pair was separated, for the first time ever, when Anders attended a different school: “Although I was sad,” said Aly, “I realised I could still help Anders be included in his classroom at the other school.” Aly with her brother, Anders, and the pair's mother, Benida When the other pupils became more curious about Anders and his likes and dislikes, Aly had to explain that he could only vocalise – and not actually speak – so she created an ‘Ask Aly’ box so that the other kids could submit questions about her brother. She said: “The most important thing, besides educating these fifth-graders about special needs, was that it really humanised my brother. “He would get to be a part of the classroom and would carry the box to them every day and interact with them while they submitted their questions, It made Anders a part of the classroom and made students more accepting of him.” When the pair was finally reunited at Oak Mountain High School, Aly began to think about graduation almost straight away. “I quickly realized that my imagination included Anders walking with me at graduation and I began to think of a way to have him there next to me,” she said.“For my mother and I, it was never a matter of ‘if’ Anders would walk with me at graduation.”

As the big day drew nearer, Aly signed up for a cap and gown and registered for her own diploma and well as her brother’s – but she kept it secret from her family and friends. Working closely with her teachers, though, she took into account the many things that could possibly go wrong: “Was he going to be mad, was he going to be content, would he be vocalising, would he be having a break down? All of these things were going through my head and I had a plan for each one in case something did not go as planned.” Aly was called first on-stage to receive her diploma. With her brother being walked quietly behind a curtained area in his wheelchair to keep him calm, she quickly exited to get him before his name was called out. Aly zoomed down the hallway with her brother in his wheelchair so that he would be happy when the big moment came. Although the principal had ordered the audience to hold all applause until the end – the moment Aly took her brother’s hand and led him across the stage – the entire hall rose to its feet and erupted into applause – including the principal herself. Original article HERE!

0 Comments

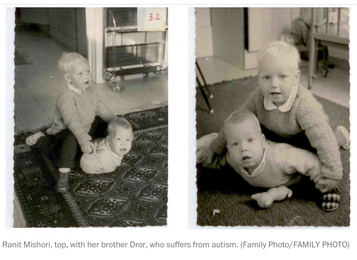

James is a special needs student who is an easy target for bullies, but five boys are on a mission to put an end to it. They promise to protect James from bullying, but what they end up doing goes way beyond that. Their camaraderie and friendship provides James with a new, bright outlook on life. Heck, it even gives me hope! Because of James’s learning disabilities, he’s forced to work in a different classroom than the rest of the kids his age. As a result, making friends is difficult. But the boys featured in the video below did not let James’s differences stand in the way of getting to know him. After seeing James get bullied, they vowed to never let it happen again. Please SHARE this heartwarming story with everyone you know!  One of the least fun moments I recall from my years of growing up with an autistic brother was when he bit me on the cheek — just in time for my class photo. I was 12 and he was 11. I went into school with visible bite marks, and when they sat me in the chair for my solo shot, I told them that the cat had done it. That’s one of the bad stories. As for a good one . . . um, to be honest, I have a hard time coming up with much. I know that people are warmed by stories of siblings who selflessly shower the disabled child with love, attention and support. I think that’s great, too. And it’s for real for some siblings. But for many of us, relating to a sibling who is on the autism spectrum can be complicated. The challenges to a warm, close relationship are many. Normal sibling rivalry doesn’t work, because it can never be a fair fight. Here’s what siblings often are up against, particularly when a brother or sister has more severe autism: ●Missing out on typical family outings, such as movies, restaurants and vacations; ●Being embarrassed to bring friends home; ●Unpredictable and sometimes violent tantrums and outbursts aimed at you; ●Being expected to grow up faster than you may want to, because you need to be the “responsible one”; ●The sense that you come second to your parents, because so much of their time and energy is focused on the one with autism. These are all fertile ground for building resentment. And then feeling guilty about feeling resentment. Because, after all, even as youngsters, we do understand that our disabled sibling cannot help being disabled. A Dearth of Research The feeling that our needs come second is echoed in the small volume of research on how autism affects siblings. Understandably, most of the scientific focus goes to the child who has the condition. (One in 88 children in the United States has some form of autism, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.) At the same time, it should be remembered that at least twice as many children confront the problems of having a brother or sister on the spectrum, says Ryan Macks, a child psychologist at Cincinnati’s Children’s Hospital and one of the few researchers on sibling impact. A fair amount of research has been done on how autism impacts the family. Most of it, however, has focused on how parents are affected.What intrigued me — both as an autism sibling and as a family physician whose patients include autism siblings — was the dearth of studies looking specifically at the sibling relationship. Moreover, the small amount of research tends to center on issues of academic performance, mood disorders and social performance, and is far from conclusive. A 2006 review of the research in the Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability found that while some researchers were uncovering “deleterious outcomes,” others were finding siblings who were well adjusted or whose challenges were of “low magnitude and non-significant.” A 2007 Harvard Review of Psychiatry article echoes this, mentioning studies that document “distressing emotional reactions such as feelings of anxiety, guilt and anger” and “more adjustment problems” as well as research noting that “some siblings benefit from their experience, others seem not to be affected.” The studies used different methodology, but even so, the inconsistency perhaps should not be surprising. Just as no two people with autism are alike, no two siblings are alike in how they adapt to their family situation. A Big Adjustment According to Macks, there are some, like me, who can’t help but recall those years as mostly difficult, with a lingering sense of a childhood that was compromised. But he suggests that such an experience is neither typical nor inevitable, as some kids weather the challenges with composure, serenity and even the belief that a sibling’s autism was actually a positive factor in their lives. The data offer only a few hints at what might determine a sibling’s response to autism in the family. Some studies reported that siblings tend to do better in bigger families than smaller; in two-parent families rather than single-parent; in families where the autistic child’s functioning is higher rather than lower. There also can be better outcomes in families of more financial means. The Good Moments Duty and the burden of responsibility aside, Smith talks about some good moments with her brother. The key, she says, is being able to keep a sense of humor — to know there are times when laughter can replace anger. “A lot of it is really funny,” Claire says. “He does a lot of cute stuff.” She recalled a recent incident in which her brother, who is also deaf, was fixated on mopping the porch. He was outside, signing to himself the instructions he had just received from his father about the chore. She chose to find his behavior funny instead of embarrassing, and to appreciate the moment. “I don’t think there are any siblings,” she says, “who can laugh at their brother having a conversation with himself and a mop.” Beyond such little moments, researchers — and some siblings themselves — are discovering that the sibling experience can produce long-term benefits. Some studies report that people who grew up with autism in the house tend to be more empathetic. “They are often able to handle difficult situations later in life. They’ve learned how to handle embarrassing situations in public; they’ve learned how to handle negotiations better,” Macks says. In fact, in stable families with “no demographic risk factors” such as a one-parent household or economic issues, Macks says, “by and large, having a sibling with autism is extensively viewed as a very positive experience, with limited long-term negative impact.” Basu and Smith agree. “I feel more responsible . . . know what it’s like to take care of someone to some degree,” Smith says. “I feel I am a little more patient than some of my friends.” Adds Basu: “It helped me become more mature” more quickly. Despite the challenges — and there are many — neither would change anything if they could. As Smith puts it: “Wishing him different is wishing him away. And I don’t want to wish him away.” This is a point Macks wants to emphasize: “Most siblings of children with autism or any other type of disability wind up doing just fine.” He believes that there is a misconception that having an autistic sibling sentences a child to “a whole range of intense struggles throughout your life.” That is not necessarily true, he says. “The majority will handle the situation quite well.” As we adjust to absorbing into our community all of the kids with autism and strive to support their unique educational, vocational and medical needs, I’d say let’s not forget the siblings, however well adjusted they may seem. Their needs must not be overlooked by parents, teachers, therapists, doctors and researchers. As for myself — now the generally well-adjusted adult sibling of a 45-year-old autistic man — the challenges are evolving. I suspect they also evolve for Smith, Basu and many others. To read the full article click HERE |

AuthorRebecca is an independent publisher working to help siblings of children with emotional challenges. Archives

April 2017

Categories

All

|

My Big Brother Bobby: A Story to Help Kids Understand Angry Feelings and Behaviors in Others

RSS Feed

RSS Feed