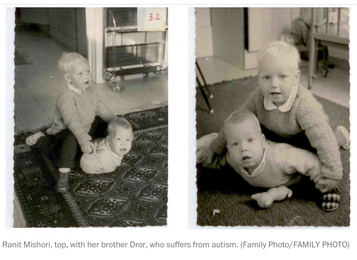

One of the least fun moments I recall from my years of growing up with an autistic brother was when he bit me on the cheek — just in time for my class photo. I was 12 and he was 11. I went into school with visible bite marks, and when they sat me in the chair for my solo shot, I told them that the cat had done it. That’s one of the bad stories. As for a good one . . . um, to be honest, I have a hard time coming up with much. I know that people are warmed by stories of siblings who selflessly shower the disabled child with love, attention and support. I think that’s great, too. And it’s for real for some siblings. But for many of us, relating to a sibling who is on the autism spectrum can be complicated. The challenges to a warm, close relationship are many. Normal sibling rivalry doesn’t work, because it can never be a fair fight. Here’s what siblings often are up against, particularly when a brother or sister has more severe autism: ●Missing out on typical family outings, such as movies, restaurants and vacations; ●Being embarrassed to bring friends home; ●Unpredictable and sometimes violent tantrums and outbursts aimed at you; ●Being expected to grow up faster than you may want to, because you need to be the “responsible one”; ●The sense that you come second to your parents, because so much of their time and energy is focused on the one with autism. These are all fertile ground for building resentment. And then feeling guilty about feeling resentment. Because, after all, even as youngsters, we do understand that our disabled sibling cannot help being disabled. A Dearth of Research The feeling that our needs come second is echoed in the small volume of research on how autism affects siblings. Understandably, most of the scientific focus goes to the child who has the condition. (One in 88 children in the United States has some form of autism, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.) At the same time, it should be remembered that at least twice as many children confront the problems of having a brother or sister on the spectrum, says Ryan Macks, a child psychologist at Cincinnati’s Children’s Hospital and one of the few researchers on sibling impact. A fair amount of research has been done on how autism impacts the family. Most of it, however, has focused on how parents are affected.What intrigued me — both as an autism sibling and as a family physician whose patients include autism siblings — was the dearth of studies looking specifically at the sibling relationship. Moreover, the small amount of research tends to center on issues of academic performance, mood disorders and social performance, and is far from conclusive. A 2006 review of the research in the Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability found that while some researchers were uncovering “deleterious outcomes,” others were finding siblings who were well adjusted or whose challenges were of “low magnitude and non-significant.” A 2007 Harvard Review of Psychiatry article echoes this, mentioning studies that document “distressing emotional reactions such as feelings of anxiety, guilt and anger” and “more adjustment problems” as well as research noting that “some siblings benefit from their experience, others seem not to be affected.” The studies used different methodology, but even so, the inconsistency perhaps should not be surprising. Just as no two people with autism are alike, no two siblings are alike in how they adapt to their family situation. A Big Adjustment According to Macks, there are some, like me, who can’t help but recall those years as mostly difficult, with a lingering sense of a childhood that was compromised. But he suggests that such an experience is neither typical nor inevitable, as some kids weather the challenges with composure, serenity and even the belief that a sibling’s autism was actually a positive factor in their lives. The data offer only a few hints at what might determine a sibling’s response to autism in the family. Some studies reported that siblings tend to do better in bigger families than smaller; in two-parent families rather than single-parent; in families where the autistic child’s functioning is higher rather than lower. There also can be better outcomes in families of more financial means. The Good Moments Duty and the burden of responsibility aside, Smith talks about some good moments with her brother. The key, she says, is being able to keep a sense of humor — to know there are times when laughter can replace anger. “A lot of it is really funny,” Claire says. “He does a lot of cute stuff.” She recalled a recent incident in which her brother, who is also deaf, was fixated on mopping the porch. He was outside, signing to himself the instructions he had just received from his father about the chore. She chose to find his behavior funny instead of embarrassing, and to appreciate the moment. “I don’t think there are any siblings,” she says, “who can laugh at their brother having a conversation with himself and a mop.” Beyond such little moments, researchers — and some siblings themselves — are discovering that the sibling experience can produce long-term benefits. Some studies report that people who grew up with autism in the house tend to be more empathetic. “They are often able to handle difficult situations later in life. They’ve learned how to handle embarrassing situations in public; they’ve learned how to handle negotiations better,” Macks says. In fact, in stable families with “no demographic risk factors” such as a one-parent household or economic issues, Macks says, “by and large, having a sibling with autism is extensively viewed as a very positive experience, with limited long-term negative impact.” Basu and Smith agree. “I feel more responsible . . . know what it’s like to take care of someone to some degree,” Smith says. “I feel I am a little more patient than some of my friends.” Adds Basu: “It helped me become more mature” more quickly. Despite the challenges — and there are many — neither would change anything if they could. As Smith puts it: “Wishing him different is wishing him away. And I don’t want to wish him away.” This is a point Macks wants to emphasize: “Most siblings of children with autism or any other type of disability wind up doing just fine.” He believes that there is a misconception that having an autistic sibling sentences a child to “a whole range of intense struggles throughout your life.” That is not necessarily true, he says. “The majority will handle the situation quite well.” As we adjust to absorbing into our community all of the kids with autism and strive to support their unique educational, vocational and medical needs, I’d say let’s not forget the siblings, however well adjusted they may seem. Their needs must not be overlooked by parents, teachers, therapists, doctors and researchers. As for myself — now the generally well-adjusted adult sibling of a 45-year-old autistic man — the challenges are evolving. I suspect they also evolve for Smith, Basu and many others. To read the full article click HERE

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRebecca is an independent publisher working to help siblings of children with emotional challenges. Archives

April 2017

Categories

All

|

My Big Brother Bobby: A Story to Help Kids Understand Angry Feelings and Behaviors in Others

RSS Feed

RSS Feed